‘Whistle’ is about more than just a whistle. It’s about time – the here and now as well as historical, and place – both the ‘North’ and the individual places of the whistles. What the whistles do is link all those big and small ideas together.

At the heart of ‘Whistle’ of course are the whistles themselves.

As with previous incarnations, it was really important to get the right whistle and make it sound right. But as the project progressed the creation of the whistles took on their own narrative.

It started at the North Yorkshire Moors Railway in October last year. We went to see an LNER B1 locomotive in action and hear what the whistle sounded like. The driver that day was a little reluctant to sound the whistle for any more than absolutely necessary for fear of upsetting the neighbours, so I could only snatch little snippets of sound but enough to get a feeling for the character of the whistle, and importantly, a pitch.

The whistle on a B1 is an ‘LNER standard design whistle’. It’s name is a little misleading as the London and North Eastern Railway had a number of different ‘standard’ designs over the years. The smaller bell-designed whistles on the large express locomotives, like ‘Flying Scotsman’ were higher in pitch but lacked a full bodied tone. The streamlined ‘A4 pacifics’ like Mallard drew heavily on their design from the massive art deco styled american locos and their whistles were similarly drawn from the US with distinctive tri-tone chime whistles. While these whistles were certainly distinctive and would have been a common sound in Newcastle up until the end of steam, these were quite complicated and expensive things to manufacture. The LNER imported their whistles from a Chicago based manufacturer, whereas the 1920’s ‘Standard Whistle’ was more homegrown in its design.

The first step to building a replica whistle was to see how the originals were built. I couldn’t find one for sale anywhere so instead with the help of the North East Locomotive Preservation Group, we took one off a loco at the historic carriage works in Darlington and took it apart to see how it went together.

Whistles were traditionally made by apprentices at loco works. They were a great way to demonstrate a wide range of engineering skills without the precision and reliability of a mechanical part. So, while there are drawings for the whistles, the parts as constructed vary from piece to piece and no two are ever exactly the same.

The whistles for the piece were to be powered by cylinders of compressed air. While the principle of sounding whistles the way had been proven with my previous piece, this time the whistles would be outdoors for over three months in all weather and would need to fire reliably every day. On top of that, at least one of the whistles would be indoors and would need to be significantly quieter so it didn’t deafen the public.

A period of testing took place over a couple of months to find out how everything behaved in various conditions. We tested various solenoid valves to see what difference they made to the overall sound volume. The same with different brands of air regulators. Whistles were fired at different air pressures to find the optimum working pressure. A whistle was sounded repeatedly in a remote part of the countryside to find out how many blasts we could get out of each cylinder of air and in a separate test, we needed to see if rain got into the whistles and what would happen if it did. Importantly we needed to find out just how loud the whistles were and also, how could we make a whistle quieter without ruining the tone?

With any project that’s not been done before, you really can’t do too much testing – as we were to later find out.

— — — —

The bell type whistle we used has been around for over a century and was built using the techniques and skills commonly used in loco building. We started off looking to see if there were any improvements we could make to the manufacturing process using modern techniques, but after a number of failed attempts we resorted to the same tried and tested techniques as the originals.

original whistle in its constituent parts

The whistles are made in three parts – a large bell over the top, a cup at the base and a central stem that sat inside the cup that made the important air gap and held the whole whistle together. The key factors in the volume, pitch and tone of the whistle are the size of the gap in the bottom cup – this creates a column of air that is split by the lip of the bell and makes the sound. The cleanliness of the tone, and to a certain extent the volume is determined by the sharpness of the bell edge. The bell edge has to sit at a sweet point above the cup for the note to ring well. If the gaping the cup is too big or the bell edge is too blunt, the tone is muddied and the volume is reduced. Get everything just right and at the right air pressure the whistle screams loudly and the bell rings with a beautiful harmonic overtone.

As with the previous whistle piece, the whistles had to be re-tuned to allow for the colder temperature of compressed air as opposed to steam in the originals. This was done with a plate cast as part of the central pillar. In the finishing stages this plate could be machined at different thicknesses and heights to give a variety to the final notes. We could have made all the whistles exactly the same pitch, but by retuning them all very slightly, there is a general dissonance between the whistles adding to a more cacophonous sound to the ensemble.

A set of blank patterns were made in steel for each of the sections. These were then sent to the foundry to be cast in brass.

The casting was done at William Lanes in Middlesbrough. Once a town synonymous with steelworks and metal foundries, William Lane is now the last working foundry in Middlesbrough. Started in the 1890’s as a brass works, the methods used have hanged very little over the past 120 or so years. The patterns are embedded in wet sand to create a negative moulds. Lamp black is used to coat one side of the mould to prevent the second from sticking so that the patterns can be removed for making the next mould. A new mould is made for every casting. The brass is prepared from copper and zinc and melted to around 900º C. It’s then poured into the mould and left to cool. Once cooled down sufficiently, the sand is knocked out of the mould and the casting is revealed. The pouring channels and other flashing is removed along with the outer layer of sand residue in the fitting room and the the castings are then sent back to the engineers for finishing.

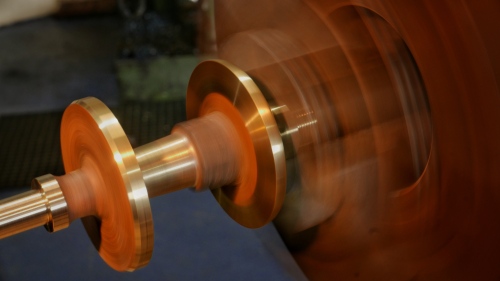

The finishing was mostly done on a lathe – the bell sections were taken down to a thickness of a few tenths of a millimetre. the angle of the knife edge being taken to around 15º (it was more accurate than that even). The cup section was similarly turned down and included a small, but vital parallel section at the top lip. The centre stem was threaded to fit inside the cup and the tuning baffle turned to the right pitch for each whistle and made a snug fit for its corresponding bell. Any gap between the bell and baffle would result in extra overtones and spoil the purity of the tone. Once all machined, the whistles were polished to a brilliant shine and numbered wth a stamp on the stem.

The finished whistles were wrapped and crated ready for installation.

Along with the drawings made from measuring real whistles, I also tracked down an original engineering drawing for a standard whistle – drawn at Stephenson Works in Newcastle for all engines built at Darlington. This cemented the heritage of the whistle we used. For me it was important that not only was the design we used from Newcastle itself, but that the engineering was done in Darlington – the birthplace of railway engineering. I wanted the build of the whistles to say something about the engineering history of the North East. Its so much part of the life blood of the region in understanding where its come from. But also vitally important with the narrative of the Great Exhibition that we can show that not only do these skills still exist but they exist at a level of excellence that can only come from that depth of heritage.

Above all, these were whistles fit for a Great Exhibition.