It’s been a while since I last revisited the ‘God’s Bridge‘ project. That’s part of the problem with long-term projects – other things come along and take over your brain space. With a shed-load more in-depth projects lurking on the horizon, I thought I’d get in quick and do a bit more before my brain gets swamped with engineering calculations and complicated maths again.

I last left the ideas looking at the underground nature of this geological anomaly in the North Pennines. It’s been an unusually dry summer here and tracing the route of the water isn’t going to happen if there’s just no water around. However, what it did do was allow me to get to bits that are normally inaccessible and have a poke around.

Last month I visited again with some proper kit to experiment with photos of those underground passages. This is what one of the tunnels looks like lit just with what little daylight gets down there. That’s one of the joys of digital photography. The Nikon sensors in particular are quite incredible in low light. In fact the light levels here were so low I couldn’t really see very far, yet with a few seconds exposure it has a whole new life.

The colours are fairly natural, although I did process them through DxO to look like I shot them on Fuji Velvia – which I would have done back in the day. It has a lovely punch to the colours without being over saturated and is particularly flattering for UK landscapes – makes the blue sky a bit bluer and the green fields a little more lush.

Anyway, much as I love exploring the North Pennines through photography – I’ve got a whole chunk here on Flickr – I was looking for something else from this.

While following the riverbed back upstream to see if I could actually find some water, the air was suddenly full of birds. Not the sparrows and starlings of towns and villages, but Oystercatchers, Redshanks, Lapwings and Curlews:

The North Pennines are a lonely landscape – big swathes of nothing. A great place for solitude. Only remote places are rarely empty and certainly never silent. Birdsong has a strange way of summoning up landscapes. Take the distant call of peacocks:

To me that’s all lawn and topiary.

In mid-spring a deciduous forest in Sweden sounded like this:

An nightingales are an incredible sound. They only sing for two weeks every year:

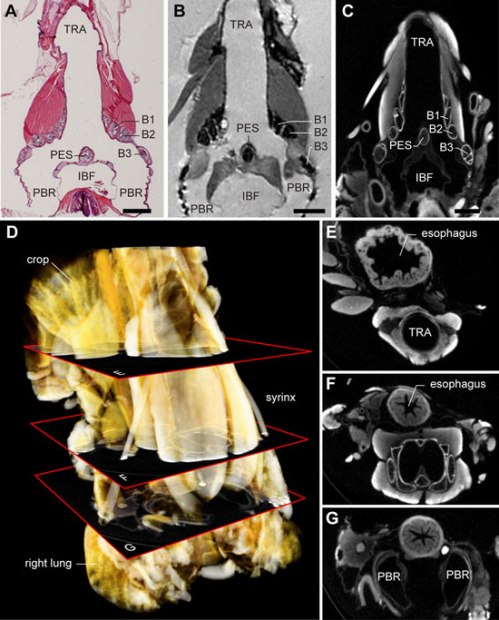

Birdsong is a fascinating thing. To start with, birds don’t whistle – they sing. The shape of their beak doesn’t come into it. It comes from the throat like us. Humans have a larynx – a bit of flappy tissue and muscle which vibrates in airflow and creates all the basic sounds we make. We further adapt them with our lips to form words for instance, but the singy bit is all voice-box. Birds on the other-hand have a syrinx. It’s a bit like a larynx, only it can make sound with air flowing in both directions – so birds don’t need to stop to take a breath. Many birds have a syrinx with two bits so they can effectively sing two different sounds at the same time. In a way they are the ultimate singing machine.

Recent research in the States have created an artificial syrinx and can emulate complex songs. There’s a bit on the BBC site here

Birdsong has been a primary source of influence to artists and composers for centuries with countless compositions based on familiar bird calls. From the 17th Century Athanasius Kircher who first transcribed the song of a nightingale into musical notation to the 20th Century French composer Olivier Messiaen’s ‘Catalogue d’Oiseaux’.

By far my favourite artworks on birdsong are ‘Dawn Chorus’ by Marcus Coates – where birdsongs were slowed down and mimed to by people in ordinary morning locations with the video finally sped back up to pitch:

and ‘Syrinx’ by Pamela Z – again the bird songs were slowed right down to a lower pitch and replicated by her voice, and then raised back up to the original pitch and speed.

However, that’s great for traditional song birds, but the sounds that fill my landscape are very different and more complex in different ways.

Oystercatchers and Redshanks are fairly straight forward. Lapwings are ubiquitous – also known as Peewits due to their mating call. However, their vocabulary is extremely varied and almost alien at times:

(the beating sound in that clip is a Snipe – it makes that sound with its tail)

By far the sound that best sums up the vast open landscapes of the North Pennines for me is the whirl of the Curlew. The sound comes from way up above and bubbles across vast distances. It trails off in a descending tone, a built in dopplar effect which seems to accentuate the vastness of the landscape.

This clip has been filtered to remove lots of the background noise and other birds. It’s really difficult to just get the pure sound of a Curlew.

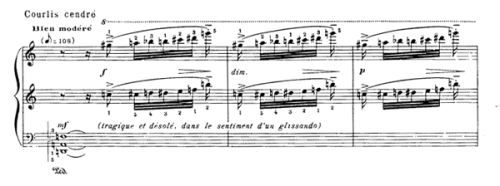

Messiaen captured the call of the Curlew and its sorrowful loneliness over the fells like this:

It’s still got that trill element and the rising tone – represented as glissandos over a decaying drone chord. It’s got a melancholy about it that feels right and is a beautiful invocation, but it’s not the sound of a Curlew.

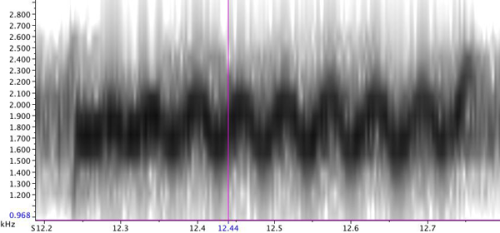

To figure out how the real sound is made I slowed the filtered recording right down to a manageable pitch and speed:

You get an idea of its construction from this sonogram of one of the repeated call sections:

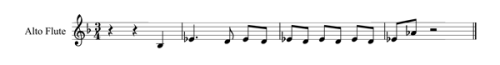

From that I transcribed a basic score. I’ve done it in 3/4, but on reflection it’s probably 6/8. and an alto flute I figure is fairly close.

so, I got the software to play it, sped it back up and it sounds like this:

Terrible.

So unbelievably bad. Though not really surprising – art is never simple. Making good art is hard work. OK, so it wasn’t a real flute playing in the first place – just a sequenced sample so lacks that natural element. Even so, this emulation of upland birdsong is far more complicated than I thought. Yet fascinating all the same. It’s going to take quite some time to get this right. I’m still not fixed on the idea of a perfect replication. I quite like Messiaen’s feeling for the bird and may yet go down that route, but there’s still something about challenging yourself and pursuing it until you get it just right and until I really have to dedicate my brain space to engineering calculations, I think that’s what I’ll do for now.