Whistle, as an installation, looks to celebrate the engineering heritage of the North of England, but also looks at who we are in the North and the sense of place.

The Great Exhibition of the North could have been anywhere north of Cheshire (I know, don’t get me started on basic geography). However, it’s ended up in Gateshead and Newcastle, so I wanted to see what defines the place in order to start a conversation about its future trajectory. Where does it come from?

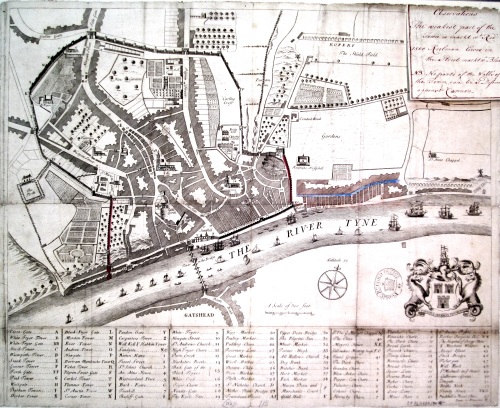

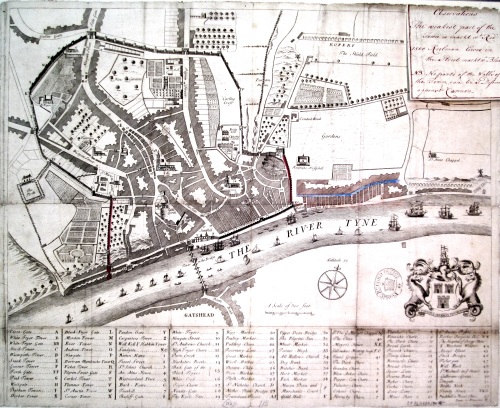

An early 18th century map of Newcastle clearly showing the route of the wall

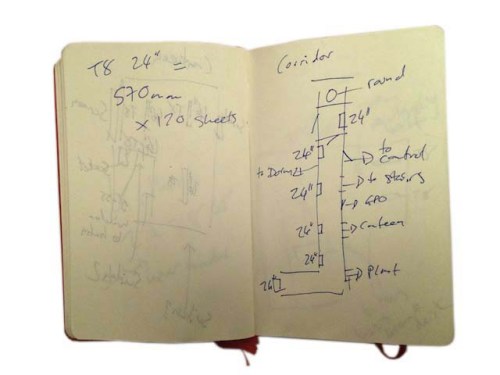

The Town Wall was built around Newcastle around the 12th Century – primarily to defend it from raiding parties from across the Scottish Border. It was typically 24 ft high (8m) and seven feet (2.5m) thick. There were six main gates – including Westgate and Newgate – and 17 towers – of which parts of six still remain. At its prime it was considered the most impressive town or city wall in the whole of England and was only breached once – by the Scots during the English Civil War. Although over the centuries it fell into disrepair, most of the wall survived into the late 19th Century and there are photographs of most of the towers before the late Victorian redevelopment of the city centre. It’s important to note that Newcastle never had a City wall – it didn’t become a city until the 1890s, by which time most of the wall was in ruins.

Although the wall is by no means complete now, there are surprisingly large amounts still standing, and even in the absent sections its route still survives.

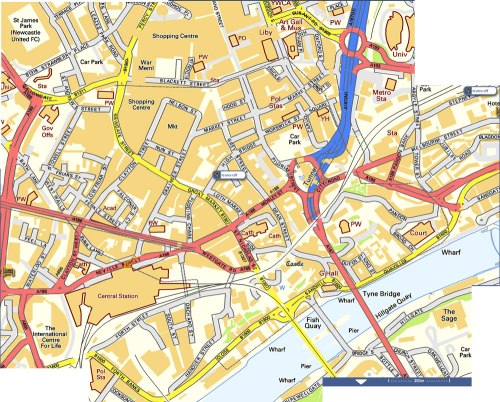

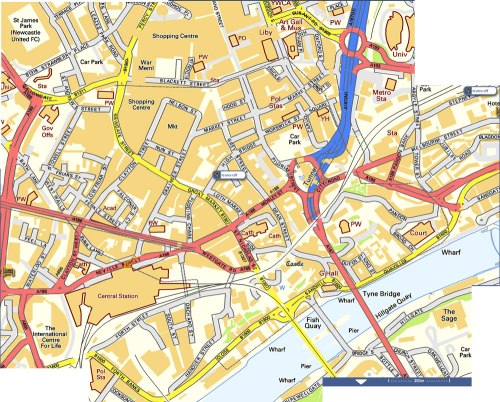

The current online map on Street Map shows the route of the wall as a dotted line

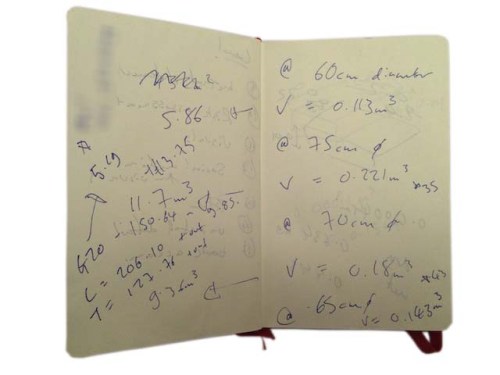

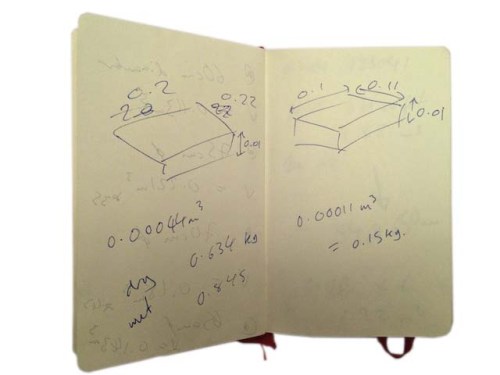

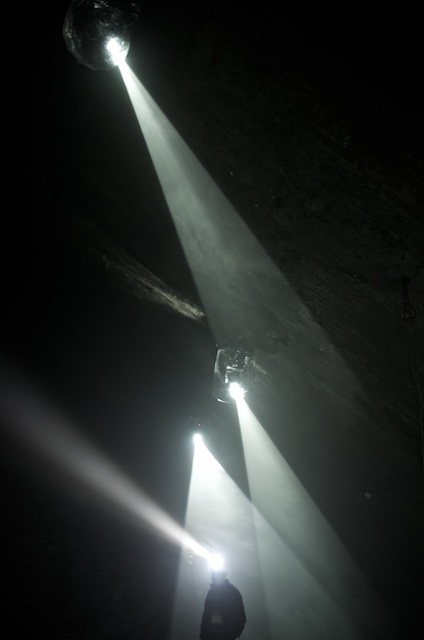

The challenge for the installation was to find sufficient sites around the wall to place whistles. As they are powered by cylinders of compressed air, the sites had to be secure. At around 130dB they are also very loud, so they had to be well away from ear-level or a safe distance away from the public. The simplest place to put them was on the roof of buildings. That meant finding and securing premises with flat roofs and good access. With a target of 18 venues across an entire city this was far from straight forward. Besides the medieval structures of the actual wall, most of the other buildings along the line of the wall were part of its subsequent history with their own architectural interest. Newcastle is a city rich in history and architectural heritage. Outside of London it has the highest number of historical buildings in England. Newcastle has 53 grade I listed buildings, 153 grade two-star, 558 grade two, 42 scheduled ancient monuments and 12 conservation areas. This in turn created its own set of issues and logistics in terms of getting permissions. In the end 17 locations were identified, which in turn held their own connection to the town wall and the history of the city:

1: Newcastle City Library – New Bridge Street West.

This was a relatively easy starting point for me as I had untaken a short residency there last year and had a good relationship with the team there. I’d already been up on the roof so I knew it was a great place to host a whistle.

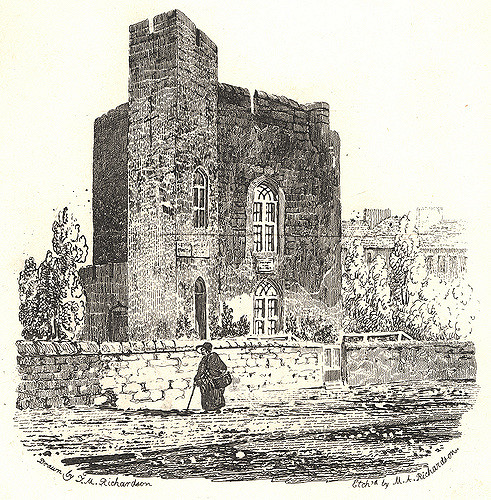

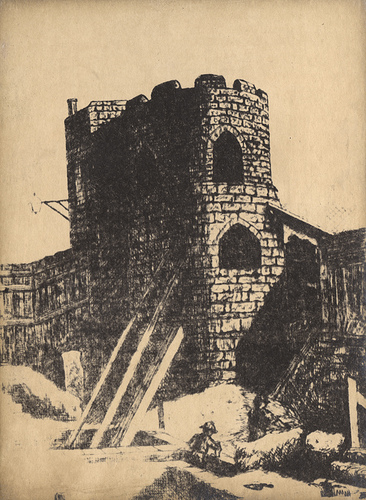

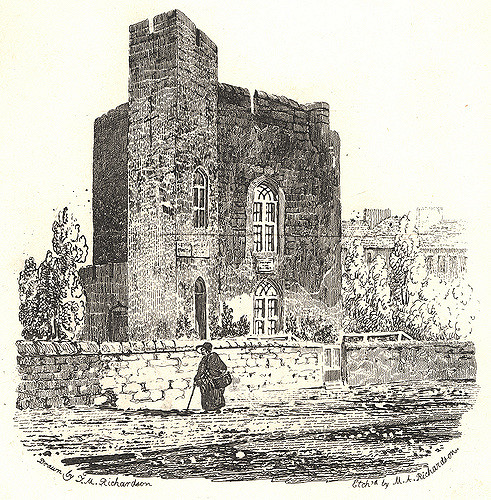

A drawing from 1825 of Carliol Tower – then a private house

The 2009 City Library building. Note the angled entrance atrium set at the same angle as the original tower (above)

The current city library was completed in 2009 and was the third library building on the site. The previous one designed by Sir Basil Spence – architect of Coventry Cathedral and Trawsfyndd power station amongst many others – was part of T Dan Smith’s vision for Newcastle’s ‘City in the Sky’ network of elevated walkways. However, by the millennium it was deemed too dark and oppressive and no longer fit for purpose and demolished in 2007. The new library was built to be future proofed as the role of libraries evolved. Built on the site of Carliol Tower on the north-east corner of the town wall, the new facade of the library echoes the idea of a tower and is orientated to match the original 12th century tower. There are some stones from the town wall recovered during the works on display inside.

2: Euro Hostel – Carliol Square.

The next tower along the wall from the library – Plummer Tower – still exists. Originally known as Carliol Croft Tower, it was home to the guild of Cutlers, then to the Guild of Masons in the 18th Century who subsequently enlarged the building to the street to how it is today. It’s now home to a team of architects who specialise in historic buildings.

Plummer Tower

The view back to the library from the Euro Hostel Roof

Unfortunately the tower has a pitched roof behind the front parapet and with no easy access up there it couldn’t be easily used for hosting a whistle. Instead, the whistle is on top of the Euro Hostel opposite. This has a clear line of sight to the whistle on the library, but also has its own town wall history. The Hostel sits on the site of the town prison. Closed in 1928, you can still see the old execution chamber out the back. ‘The Ware Rooms’ bar is named after the place where one of its former inmates hid his stash of stolen jewellery.

3: Holy Jesus Hospital – City Road

The motorway slices unceremoniously through the line of the wall, with the mainline railway intersecting it from the opposite direction removing all traces of the wall itself. The next tower along the line – Austin Tower – probably lies somewhere beneath Manors Car Park.

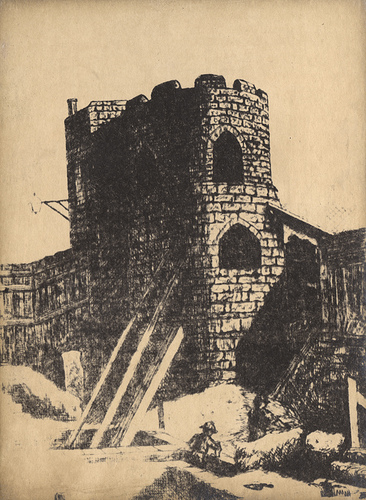

Austin Friary Tower. The part to the right of the door is original and contemporary with the Town Wall. To the left is the wonderful helix ramp on Manors Car Park. The original Austin Tower lies beneath the car park somewhere.

The next nearest spot is Austin Friar’s Tower. Austin Friary was home to a group of Augustinian monks from the 13th Century. The 14th Century tower is all that remains of the friary, although it is now attached to Holy Jesus Hospital – a 17th century building used to offer lodgings – hospitality – to freemen of the city. This is now one of the oldest brick-built buildings still in use. The tower was altered in the 16th century after the dissolution of the monasteries, and became a strong room to protect valuables in the event of the town wall being breached.

The Whistle was to have been installed on the roof of the tower – now in the hands of the National Trust – however, the access costs and logistics were escalating rapidly so this one had to be postponed at a late stage.

4: Sallyport Tower – Tower Street

This building straddles the meeting point of the town wall and Hadrian’s wall. Built on the base of a roman tower, this is the oldest site on the wall. The gate gets its name from being the route the army would rush out to engage with any attacking party – where they would ‘sally forth’. The tower was mostly destroyed in the siege of 1644 – the only time the wall was breached. The building was restored in 1716 with an extension on the top by the Guild of Shipwrights and Carpenters who used it as a meeting room.

Sallyport Tower. The foundations are Roman, the ground floor is mostly the original wall. The upper storey is a 17th century addition

The building is currently being run as a wedding venue so the whistle isn’t permanent here.

5: The Jolly Fisherman on the Quayside – Milk Market

From Sallyport Tower, the wall curved gently down to the river. There was no wall as such built along the quayside with the river itself forming the main defence.

The Tyne Inn pub on the corner of Milk Market. Note the use of stone on the next door building following the line of the Town Wall

The pub most recently known as ‘the Jolly Fisherman’ or the ‘Waterline’ or even the ‘Tyne Inn’ is a grade II listed building built as a pub in 1904. This sat on the corner of the Milk Market and was once part of the busy quayside activity. The ground floor of the building along Milk Market reflects the line of the wall that ran down to the river along this point.

The pub is now part of the ‘Tomahawk’ restaurant on the Quayside. The whistle here sits on top of the hanging sign bracket.

6: Live Buildings – 55 Quayside

This relatively new building is one of the few sites without historical precedent. Sandwiched between a 19th Century quayside inn and the 18th century customs house, in never the less has an unparalleled view of the river and directly opposite the Sage building. From the balcony you also see the rooftops of the neighbouring buildings with a clear view of the bell on the roof of the Customs house next door. A reminder of a time when sound played a bigger role in signalling and communication across the city.

Probably the best view from the Quayside. Next door is the Customs House, complete with bell on the roof

The building is now home to Zerolight – one of the ever-growing number of tech and software companies in the city. Here they develop virtual and augmented reality technologies for the luxury car market.

7: Guildhall, Sandhill

The original plan was to site a couple of whistles on the towers of the Tyne Bridge – it being an unmistakable icon of the city. However, every summer the bridge and surrounding buildings become nesting sites for rare kittiwakes. These small sea birds normally nest on cliffs above the sea, but since the 1950s this has become one of only two inland nesting sites for the birds in the world. So the Tye Bridge and many other sites along the quayside cannot be used or accessed during the breeding season.

The whistle installed on the roof of the Guildhall. The original bells can clearly be seen on the far end

The Guildhall beneath the Tyne Bridge is one of the frequently used nesting sites. However Kittiwakes are fussy birds and only nest where they can see water. So the side facing away from the river is free from nesting birds.

The Guildhall is a Grade I listed building dating from 1665. Built as the seat of local power it was home to the various Guilds who had their individual meeting rooms at each of the castle towers. It was the town hall until the end of the 19th Century when the town became a city. It’s been redesigned and extended at several points over the centuries – the curved east end was designed for the fish market by notable local architect and town planner John Dobson. On the roof is a cupola with a chiming clock. However, below the clock on the north side is an earlier set of bells with the chiming mechanism within the central roof. More reminders of the use of sound within the cityscape.

8: Quayside Inn, 35 Close

This is the last surviving of the original quayside warehouses. From the 16th century this part of the riverside was a maze of narrow streets and houses with numerous warehouses lining the quayside beneath where the High Level Bridge is today. Both sides of the river were busy with ships being loaded and unloaded.

On the 6th October 1854, a fire broke out at Wilson’s worsted mill on the Gateshead side of the river. This rapidly spread to a nearby chemical works which subsequently exploded. Stones were shot hundreds of metres across the river. The force of the blast destroyed the riverside buildings in Gateshead and ripped off the roofs and blew in the shop fronts on Newcastle’s quayside. Burning debris quickly spread through the densely packed buildings along the quayside on the Newcastle side and before long the twin fires decimated both cities. The fire could be watched from the newly opened High Level Bridge.

35 Close sitting beneath Stephenson’s High Level Bridge.

What is now the Quayside Inn is the only building with a riverside frontage to survive. This is now a Grade II* listed building. The whistle is on the outside of the loft doors overlooking the river. This building would have been right on the edge of the river. The quayside has since been infilled so it sits nearly 10 metres in.

9: The Town Wall, Orchard Street

This is one of two lengths of intact town wall remaining. About 80 metres of the wall, most of it the full eight metres high, run along Orchard Street from Forth Street. A fruit orchard grew along this stretch of wall – hence the name. In the 19th century a works building was built into the west side of the wall where you can still see the post holes for the rafters.

The wall along Orchard Street

A whistle was planned to sit in top of the wall along the walkway. However, access costs started to escalate so this site had to be dropped late on.

10: Central Station main concourse

From Orchard street the wall took a straight line across where the railway now stands before curving round through what is now the main station . With commanding views both to the west and south over the river valley there were three towers within the footprint of the station: Neville Tower stood at the far east end of the platforms and was the meeting hall for ‘the company of Wallers Bricklayers and Plaisterers’. West Spital Tower stood more or less on the concourse and got its name from the nearby St Mary’s Hospital. Stank Tower was on the corner of the entrance portico.

The elegantly sweeping curve of Central Station’s roof

Central Station sits on an elegant sweeping curve, accentuated by the vast ironwork roof. The original station building was designed by John Dobson and featured the first great train shed roof, built the same year as the William Paxton Great Exhibition Palace and so considered the cutting edge of architecture of the time. John Dobson won a medal in Paris in 1858 for inventing the rollers used to create the curved girders. The station was officially opened by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1850 when it was mostly just a roof and some facades. The main station buildings weren’t finished in time! Their crests can be seen in the roof trusses.

11. Central Station entrance portico

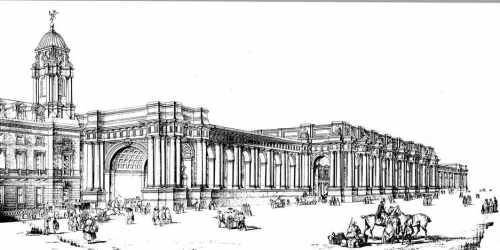

Stank Tower sat on the outside corner of the entrance portico – just beyond the Cafe Nero kiosk. The original plan for the portico was for it to run the entire length of the station . the arches becoming alcoves each with its own statue. However, the scale and associated cost was revisited and a simpler portico was built as survives today.

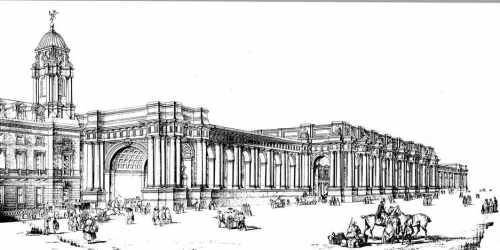

The original plan was for a portico running the entire length of the station

Central Station’s John Dobson lineage and importance in the development of the railway station has earned it a Grade I listing. The connection between the railway engineering aspects of ‘Whistle’ and its location are undoubtedly strongest at the station. By having two whistles within the station – both indoors and in close proximity, the station is also by far the loudest and most obvious location. The dissonance between the whistles and the lively acoustic make it quite an experience on its own.

Whistle in a much more modestly sized entrance portico

12. Gunner House

From Stank Tower the wall crossed Neville street diagonally and continued along that line up Pink Lane. Gunner House takes its name from Gunner Tower which stood on the site. You can see the base of the original tower outside the Town Wall pub next door (which also serves a very drinkable and exclusive ‘Toon Waal’ beer). Gunner Tower became the meeting room for the ‘incorporated company of Slaters and Tylers’. The wall along Pink Lane was removed by the 19th Century.

A drawing from around 1825 showing Gunner Tower as it remained then. The current Gunner House sits next door and is home to a Subway sandwich shop

14. Heber Tower

I know – there’s no number 13. Certainly unlucky for some – the site of whistle no.13 was never granted permission so was cancelled quite early on.

No. 14 however is on the wall itself. Heber Tower sits at the corner of the most complete section of wall still standing. West walls runs from Durham Tower, past Heber Tower, Morden Tower and ending with the remains of Ever Tower. Like Durham Tower, Heber Tower survives almost intact as when it was first built in the 13th century. Access to the walkway is via one of two internal staircases. Along the top of the wall you can clearly see the walkway and how it went through the intermediate sentry towers. From the 15th century the tower became the meeting place and was maintained by the Guild of Felt-makers, Curriers, and Armourers. In the 19th century the tower was used by a blacksmiths.

View along the top of the wall from Heber Tower looking towards Merton Tower. The Fosse – or Town Ditch – can just be seen on the left. In the foreground is one of the 13th century carved heads

The top of the tower overlooks the last remnant of the ditch that ran the length of the wall as part of the town defences. The parapet wall on the tower is pretty much all intact, complete with 13th century carved heads on the inside keeping guard. The whole of the West Walls is Grade I listed and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Another of the carved heads on the top of Heber Tower

15. St Andrew’s Parish Church

The churchyard at St Andrews, sitting amongst the hustle and bustle of a busy city, is a surprisingly calm and quiet space. The church was here long before the wall. the records show how graves had to me moved to allow the wall to run within its grounds. There is another large intact section of wall within the grounds – the shops along one side of Gallowgate were built on top of the wall – the present Gallowgate being much higher than it originally was – remember this would have been a ditch too. In the corner would have stood Andrew Tower.

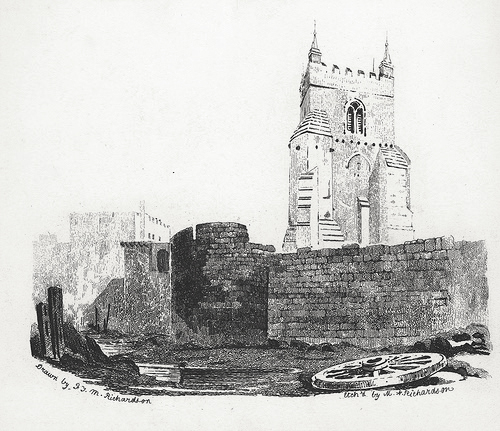

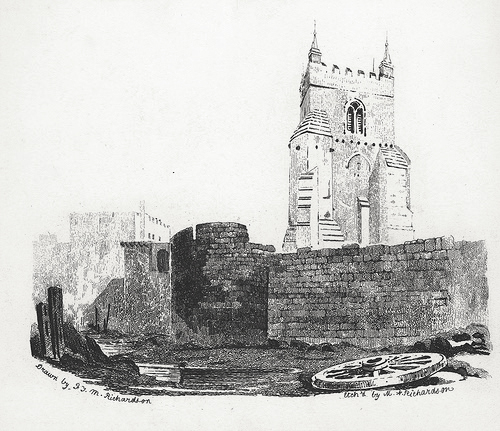

A drawing C1825 showing Andrew Tower with the parish church tower behind. In the distance is the imposing Newgate

The church dates from the 12th century although much of the existing church dates from much later and includes a Lady Chapel by John Dobson. outside the porch is the grave of composer Charles Alison, who died after being caught in an unexpected blizzard in May.

St Andrew’s Church Tower is no strong enough to cope with swinging bells any more. Instead the bells hang vertically with electronic actuators powering the hammers

The Whistle here is situated on the top of the tower. Much of the tower survives from the 12th century, notably the stone spiral staircase up to the top bell chamber. The tower can no longer take the weight of swinging bells, so these are now static and rung by means of actuators on the hammers and controlled by a timer in the church.

16. High Friars, Intu Eldon Square Shopping Centre

From St Andrews the wall crossed Newgate with a major gateway in the wall. Newgate was the largest structure in the wall and enlarged with a fortified barbican in the 1390. From there the line of the wall passes beneath what is now part of Eldon Square shopping centre. The original Eldon Square was an elegant formal square designed by John Dobson. This was controversially demolished in the 1970s to make way for the current shopping centre. The outside wall along the south side of Blackett Street follows the line of the town wall. Although there is no trace of the actual wall, its heritage lives on in the names of the quarters within the centre. The High Friars Mall follows the line of Friars Chare that ran through the nunnery gardens there. The opening space for the escalators beneath Eldon Leisure sits exactly on the site of Bertram Momboucher Tower and its square atrium space echoes the ghost of a tower. The original tower takes its name from Bertram Mombowcher – one of the high sheriffs of Northumbria during the reign of Edward III. This part of the town became the poorest area by the mid-19th century so atypical slum clearing fashion it was torn up and rebuilt as Blackett Street. The stones from the wall were reputedly reused to line the new sewers.

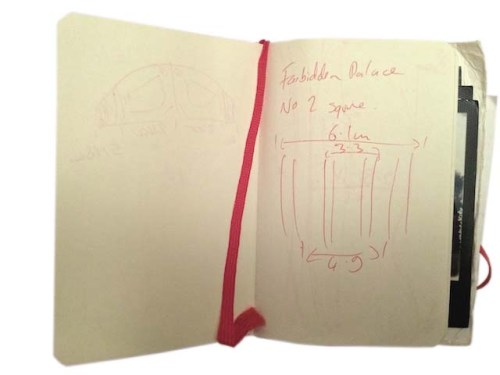

The current site of Bertram Momboucher Tower inside the shopping centre

The whistle inside the shopping centre is the closest to the public and as it’s in a relatively enclosed space has had to be specially engineered to be significantly quieter so as not to deafen shoppers. It’s still very loud though!

17. Monument entrance, Intu Eldon Square

the last whistle in the piece sits overlooking the statue of Earl Grey. The outside edge of the shopping centre sits directly over the site of Ficket Tower. The entrance to the centre follows the line of Friars Chare and the wall would have run alongside it next to the current Blackett Street. You can see the site of Ficket Tower in the distinctively rounded northern flank of the entrance. The whistle here is on the roof.

The rounded end to the north face of the shopping centre echoes that of the Town Wall towers and Ficket Tower that once stood on the same spot

From here the line of the wall runs along Blackett street, across Pilgrim Street on Pilgrim Gate and back to Carliol Tower. Pilgrim Gate was demolished in 1802 when the gate became too narrow for the wagons of the day. When it was demolished the builders discovered a 24 lb cannon ball in the walls – a remnant from the siege of 1644.

All in the piece runs around 2.2 miles (3.5 km) of the town wall. Of the sites there are three Grade II or II* listed, five Grade I listed, two scheduled ancient monuments, and part of a UNESCO World Heritage site. This is by far the most complicated piece I’ve done in terms of securing permissions – with over 20 landlords, tenants and licensing bodies to appease. The install documents alone run to nearly 200 pages.

But the complexity of the various locations and their individual connections with the history of the Town Wall, for me, adds so much more depth to the overall piece and cements the piece with the place in a way that simply wouldn’t work anywhere else.

Read Full Post »